Journalist Meg Bernhard (New York Times Magazine, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker) wrote an in-depth feature about The Mojave Project for the High Country News December 2022 issue. Meg understands what is central to MP and did a wonderful job sharing my perspective and the creative/activist drive behind the project. Read the feature here: https://www.hcn.org/issues/54.12/features-arts-culture-an-expedition-through-kim-stringfellows-mojave.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Mythbusting in the Mojave

On a cold, clear evening last winter, I stood on my father-in-law’s porch high on a juniper-speckled ridge on the southwestern edge of the Mojave Desert. To the south, the San Gabriel Mountains were silhouetted against the sky-glow of Los Angeles, the only visible indication that a seething mass of 13 million people lived only 20 air-miles away. I considered how the early white colonizers — completely disregarding the Indigenous peoples who have inhabited this landscape for millennia — portrayed the Mojave as a desolate and barren wasteland.

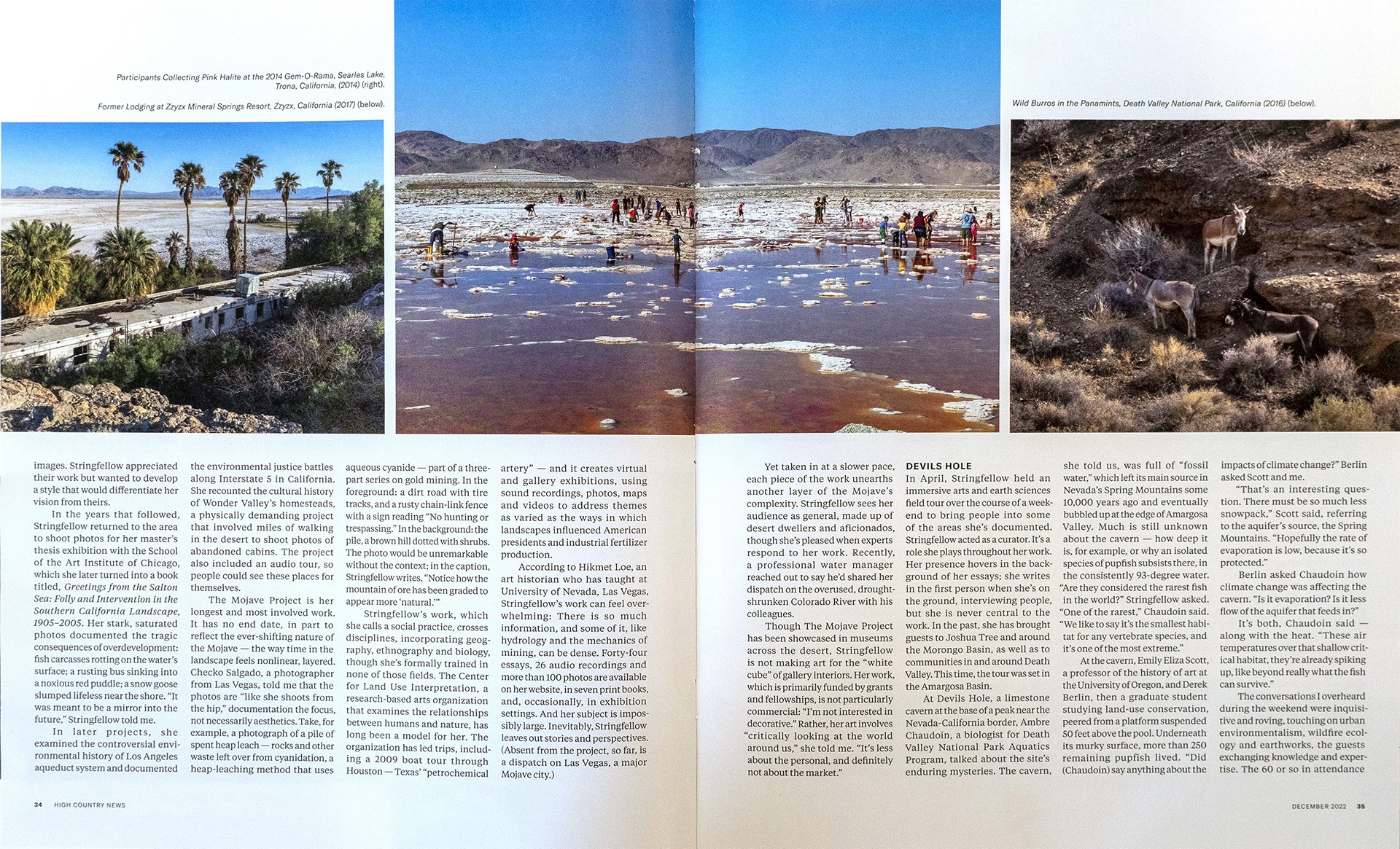

Perhaps this was out of ignorance. Then again, by depicting the Mojave as no more than a blank canvas, they felt free to exploit and abuse it however they wanted, imposing their own desires and dreams on a land they never understood. By imagining it as a wasteland, in other words, they and their successors could turn it into one.

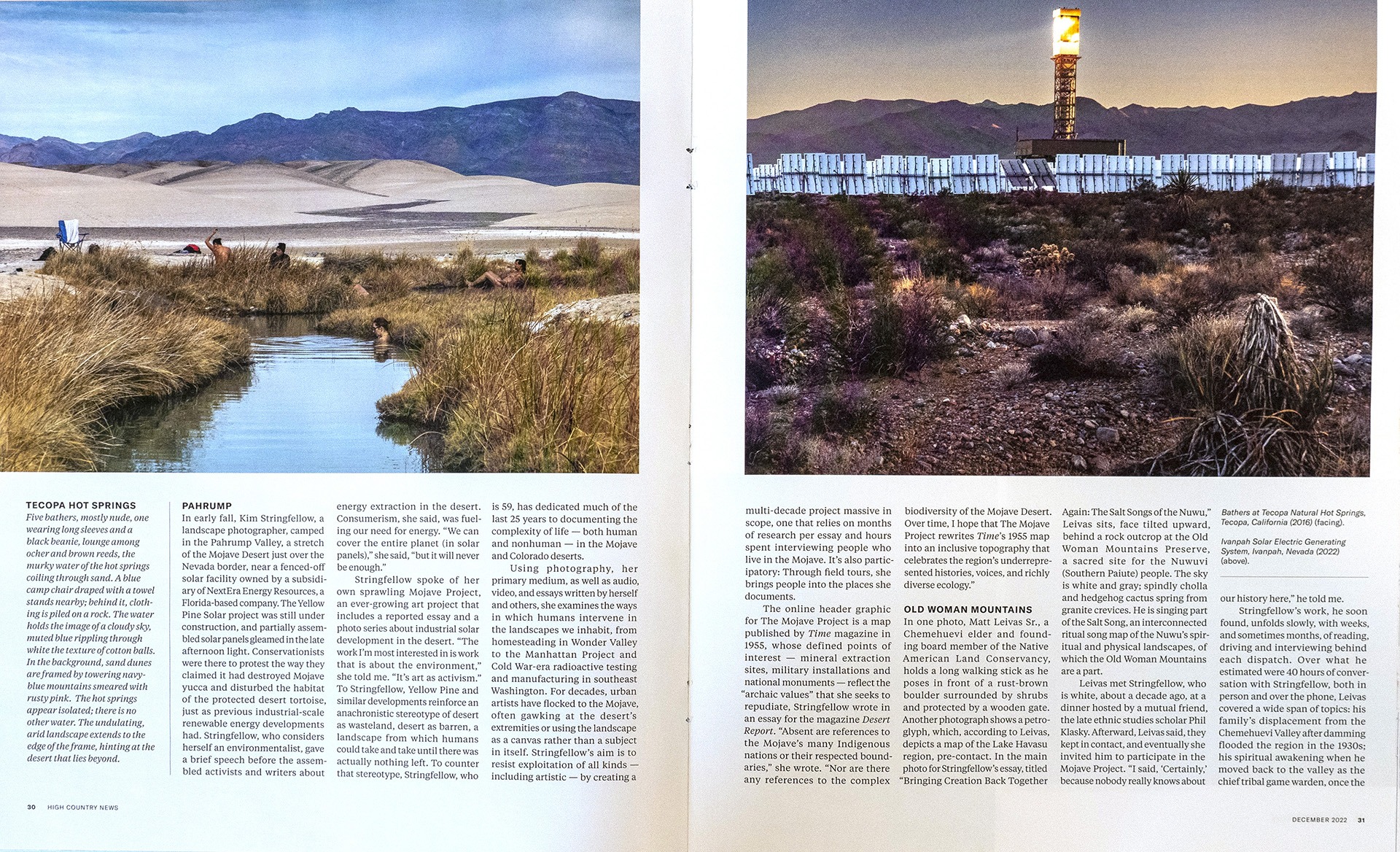

From where I stood, it looked like they succeeded. To the north, the Antelope Valley has become the place where LA exiles all the stuff it needs, but doesn’t want to look at: gravel pits and transmission lines; solar facilities and sprawling mono-architecture subdivisions; prisons and Air Force bases. Red lights atop wind turbines flickered in syncopated rhythm along the base of the Tehachapi Mountains. The Los Angeles Aqueduct reflected the day’s last light, a pink-tinged silver eel slithering across the dusky landscape.

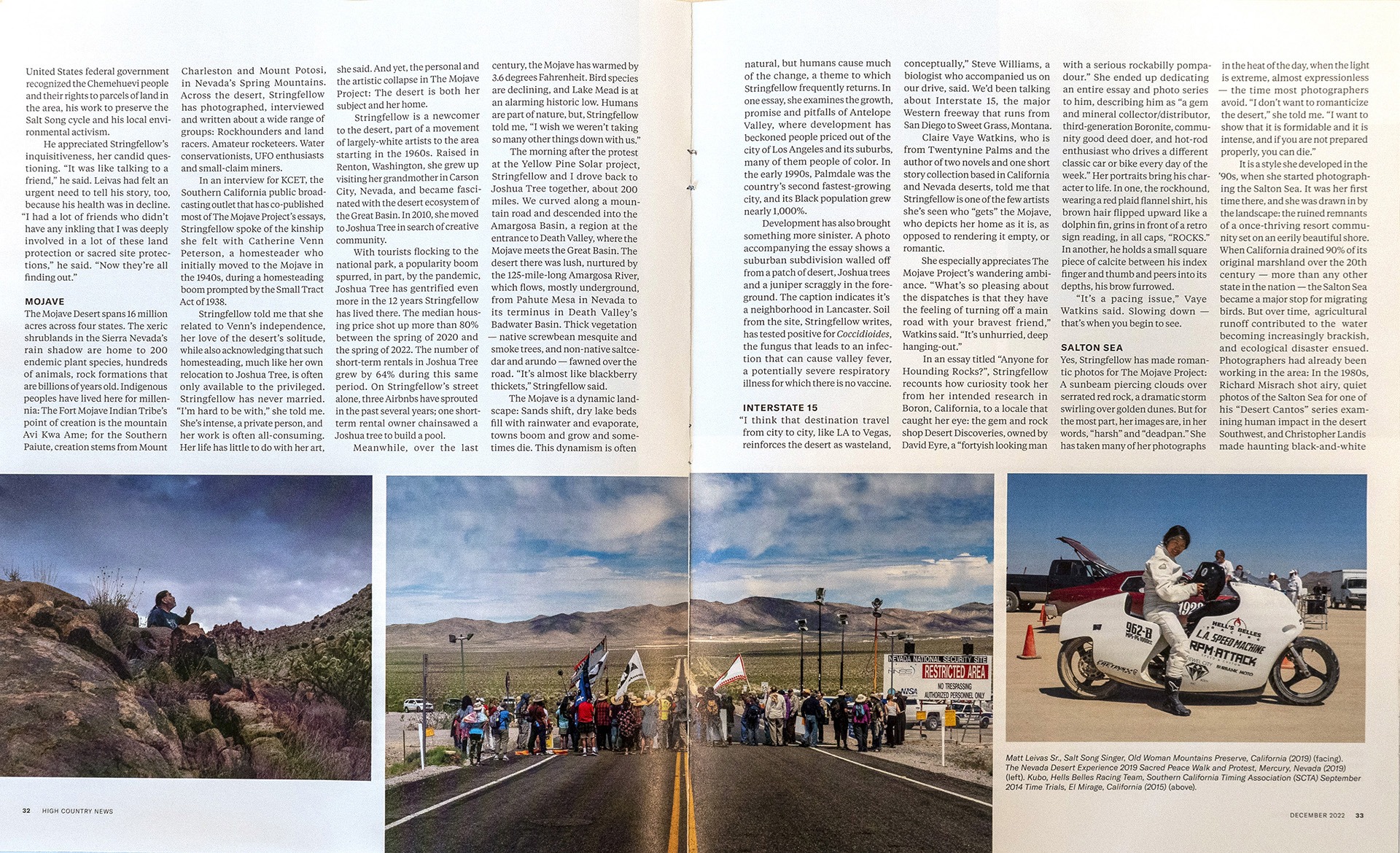

Yet the Mojave is also a place — if “place” can describe an expanse so vast it warps your sense of space and time — full of wonder and weirdness and diversity and beauty. It draws eccentrics and artists, misfits and misanthropists, the priced-out and disenfranchised, making for a vital human community scattered across the desert. Artists like Kim Stringfellow — profiled in this issue — are trying to capture and communicate the Mojave’s unique qualities to permanently dismantle the wasteland myth.

And a coalition of Mojave Desert tribes — descendants of the people the “wasteland” moniker was largely designed to erase — is leading an effort to establish the Avi Kwa Ame National Monument on southern Nevada lands held sacred by Yuman tribes. This enormous swath of the Mojave has stubbornly resisted industrialization; it remains ecologically abundant and culturally significant, a place where springtime wildflowers carpet the rocky earth with stunning yellows, reds and blues, and where anthropoid Joshua trees enthusiastically wave their prickly arms against the blaze-orange sunset.

It is all a testament to the fact that the Mojave has never been a wasteland, but rather a land of immense, indomitable vitality and resilience. Despite everything, the Western landscape and its diverse inhabitants, both human and non-human, endure, tough and tenacious and vividly, uniquely alive.

— Jonathan Thompson, acting co-editor High Country News